Each year, there’s often one game that dominates my time for a hundred or so hours. Last year it was Elden Ring. Previously it was Breath of the Wild and The Witcher 3. Back in 2017 it was Persona 5.

I loved it. I’d never previously played a game in the Persona (or Shin Megami Tensei) series. Its mix of social management and JRPG was like nothing I’d experienced, its soundtrack was infectious, its teen drama thrilling. It instantly became one of my favourites.

It also left me intrigued about its predecessors, which are finally now available beyond PlayStation with the release of Persona 3 Portable and Persona 4 Golden on Switch and Xbox. Working backwards, I jumped into P4G – a game many consider to be a high point in the series.

I’m so disappointed.

First released in 2008 and followed by the Golden version on PS Vita in 2012, this launch is something of a retro re-release. Yet with its outdated stereotypes and dialogue filled with misogyny and homophobia, P4G has not aged well. This isn’t a fine red wine, but a bottle of sparkling that’s gone flat.

It may seem unfair to critique a Japanese game from over a decade ago for having outdated views. After all, it’s a product of its time and of its culture. But after the success of Persona 5, this release of P4G is bringing the game to a new (more global) audience. It’s not beyond criticism from fresh eyes; in fact, this is an opportunity to reflect on the past and appreciate how far representation in games has come.

As with other games in the series, P4G follows the same dungeon-crawling JRPG and social simulation structure for a formulaic experience. You play as a young man who moves to a new school in a new area of mysterious happenings. You form bonds with your fellow schoolmates – the jock, the pretty one, the feisty one – who each discover the powers of their own Persona in a parallel world contained within technology (here a TV, in P5 a mobile phone). The game unfolds in a strict calendar format, each day full of choice: dungeon crawling, shopping, socialising, and more. It’s even got the same weird Velvet Room where your Persona powers are manipulated.

P4G does have its charm. The smalltown Japan setting and murder mystery story offer a more intimate slice of life vibe away from P5’s hectic vision of Tokyo. The smaller scale feels more manageable too. And the j-pop music, as always, is pure joy. Yet throughout my time with P4G so far, I can’t shake the feeling of overfamiliarity.

It’s the poor representation that has truly soured my time with the game, however. P4G is rife with misogyny. Female characters exist almost always under a male gaze, their worth directly relating to their looks. They’re almost constantly hit on, be it by their friends or even their creepy teachers. The two girls the hero befriends are heavily stereotyped between the quiet pretty one and the outspoken nerdy one – it’s clear which is considered more desirable. That’s made explicit when male friend Yosuke directly asks the player which girl he’d rather date, as if fancying at least one of them is inevitable. I chose neither and my character’s courage increased: it does take courage to not fit societal norms, after all.

Speaking of societal norms, let’s discuss Kanji.

Major story spoilers follow.

Kanji is a fellow student who has dropped out of school to beat up the local biker gang. He’s aggressive, unlikeable, and a delinquent.

He’s also gay, though not explicitly. He’s just portrayed using harmful stereotypes that are at best awkward and at worst downright homophobic. Playing through his story arc is deeply uncomfortable.

The Persona games thrive on psychoanalysis and purport to tackle tough subject matters. Its teen protagonists are on a mission to assist characters with self-acceptance by – of all things – exploring a dungeon of the mind that reflects their repressed inner-desires and subconscious demons. Kanji is no exception. It’s clear he’s suffering from internalised homophobia – self-hatred due to his sexuality. He lashes out at others and is quick to temper because he’s struggling to accept himself. Handled sensitively this could have been an ideal exploration for a Persona game, with the series focused on self-reflection and acceptance to overcome trauma.

Except it isn’t, for two reasons: the lack of empathy shown by the other characters, and Kanji’s own lack of acceptance or resolution.

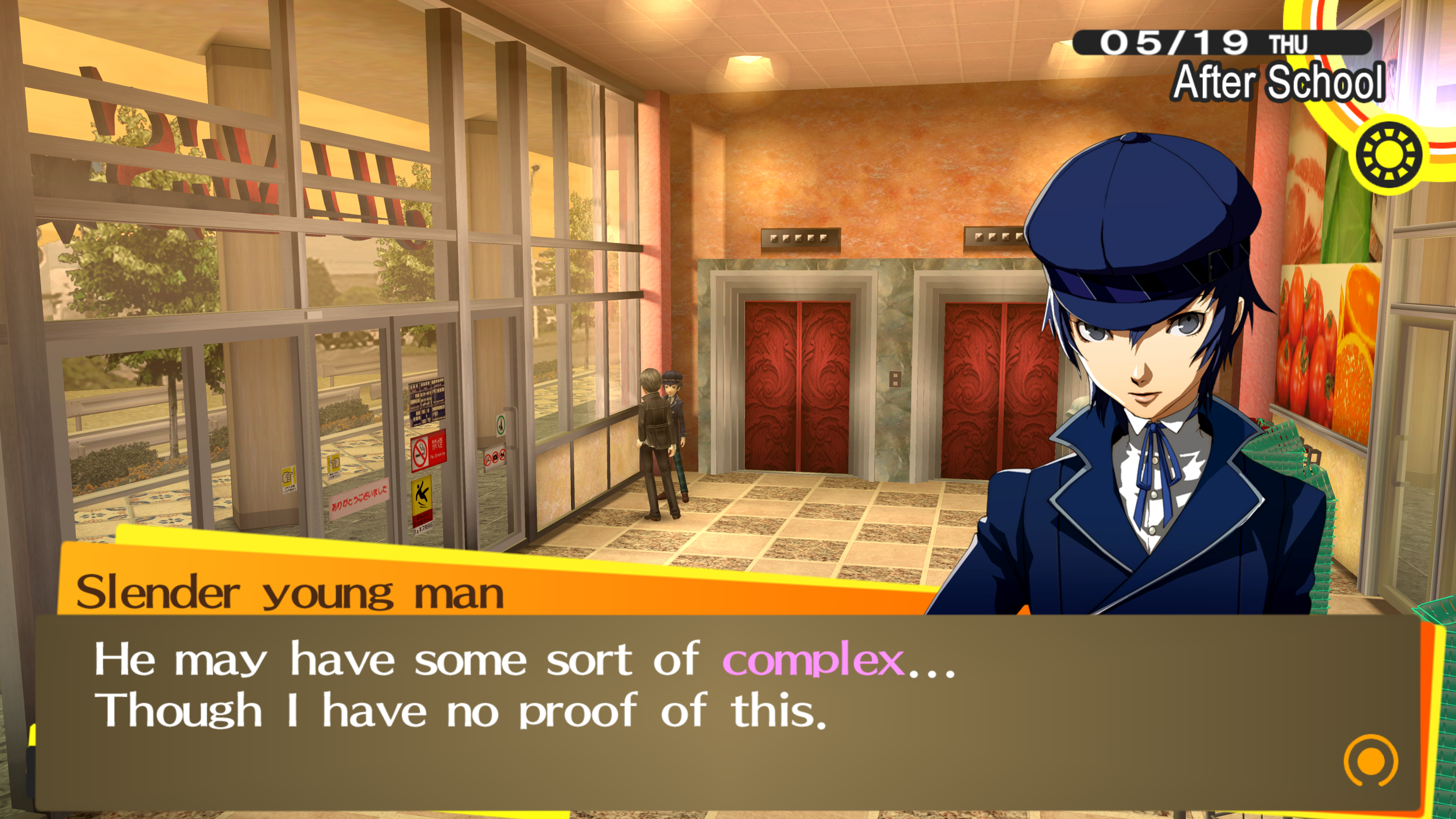

“He may have some sort of complex,” says one character describing Kanji, as if sexuality is an issue to be cured, while others describe him as strange. When questioned, Kanji insists “this ain’t what you think!”, afraid to open up.

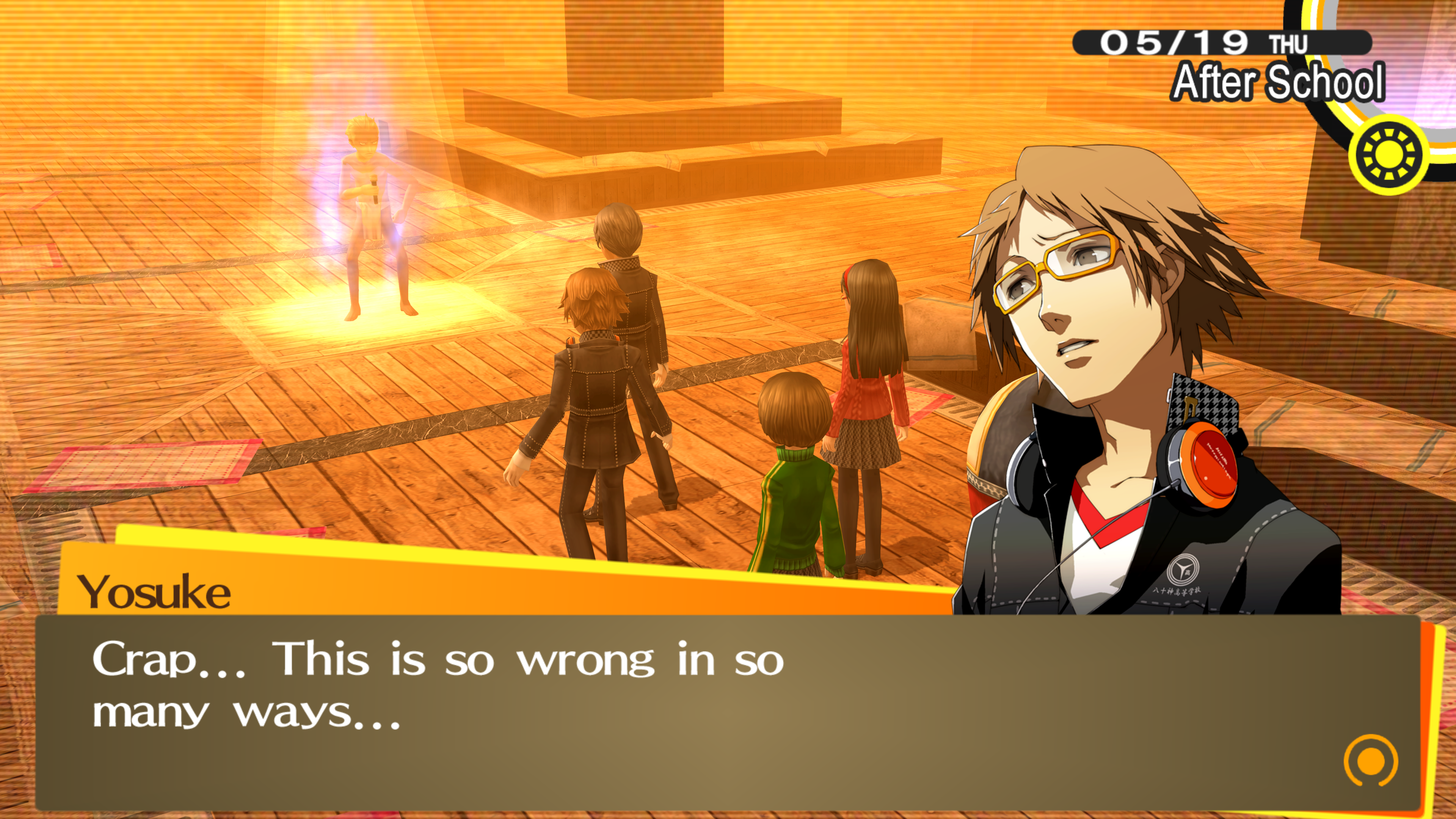

That is, until the dungeon. For Kanji that takes the form of an all-male seedy bathhouse bathed in scarlet and accompanied by porno saxophone music, around which Shadow Kanji – an evil version of himself – cavorts in nothing but a towel. “This is so wrong in so many ways,” responds one character. Kanji’s sexuality is clearly coded as gay, but rather than accepting him the other characters see this as predatory and odd. Perhaps too the bathhouse represents Kanji’s own fears of homosexuality, again reflecting his own internalised homophobia.

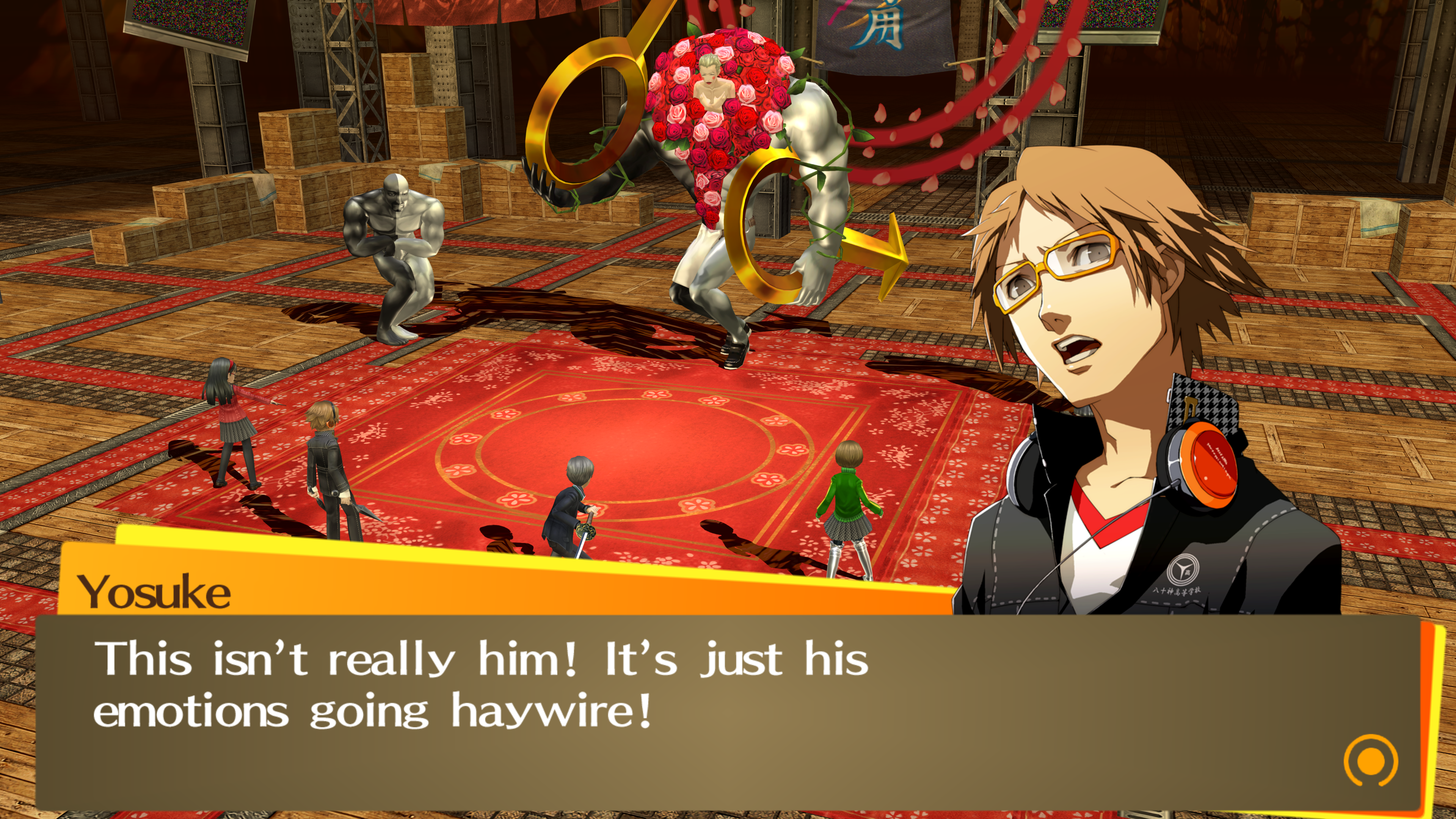

Later the group must battle Shadow Kanji: a hyper masculine demon with bulging muscles and oversized male gender symbols for weapons. “This isn’t really him! It’s just his emotions going haywire,” says one character. Sexuality is clearly perceived as something that can be cured and as long as he has these intrusive thoughts, the group must battle to save him somehow.

Really, the only way Kanji can be saved is to accept his own desires – but he never does. When Shadow Kanji screams “accept me for who I am!”, the real Kanji refuses. “Can’t believe something like this is inside me,” he says.

And then the real kicker: Kanji, it turns out, isn’t struggling with his sexuality at all. He simply has a fear of rejection, from either gender. He’s interested in typically feminine pursuits like sewing and worries that this makes him less of a man. After all the sexualised imagery and clear connotations of homosexuality, Kanji never comes out. Instead he simply accepts his fear of rejection. This is the “strength of heart” he shows, which isn’t strength at all. It’s a bait and switch by the writers that utterly undermines the character and heightens feelings of shame.

Crucially, the word “gay” is never used explicitly – before or after Kanji’s change of heart. Despite heavily implying he’s gay, this is not once acknowledged by Kanji or another character. Instead it’s swept aside, pushed down, ignored, a choice that’s quite frankly dangerous to any LGBT+ players questioning themselves.

Of course, this sort of exploration was daring when the game first released. Yet sexuality and the existence of LGBT+ people is not a salacious mystery to be solved. The treatment of Kanji simply reveals a profound misunderstanding of what it means to come out.

Even worse, Kanji’s acceptance is tied to misogyny. “Girls are so loud and obnoxious, so, y’know…I really don’t like dealing with ’em,” Kanji tells the group after the dungeon ordeal. “I guess I wasn’t really afraid of girls, I was just scared of people in general.” Not one of the other characters pulls him up on his comment.

Since finishing this story arc I’m yet to continue with P4G, but the poor representation doesn’t stop there. Writing for Gamespot back in 2013, Carolyn Petit notes that later in a camping trip the male characters ask Kanji “are we gonna be safe alone with you?”, depicting their own fear of homosexuality. When Kanji says he has no problem being around girls, he’s even asked to prove it. Rather than addressing these prejudices, homophobic comments are simply left unchallenged – nothing has been resolved.

Then there’s Naoto, described as a “slender young man” when first met. He’s a young detective who uses male pronouns. His dungeon, as Petit writes, is a metallic bunker in which he declares he will embark on a “bodily alteration process” resulting in “the moment of a new birth”. Shadow Naoto says Naoto is “such a cool, manly name” but that “a name doesn’t change the truth. It doesn’t let you cross the barrier between the sexes”.

The implication of all this is that Naoto is trans, but rather than accepting this, another bait and switch occurs. Naoto says that being female “doesn’t fit my ideal image of a detective” and states “though I will one day change from a child to an adult, I will never change from a woman to a man”. Naoto is then treated by the other characters as a girl, and is suddenly flirted with by men – the troubling inference being that Naoto has been female all along and simply chose to wear men’s clothing, rather than any deeper exploration of gender.

This sort of representation is not specific to P4G. Persona 5 featured two predatory older gay men who are sexually aggressive towards a minor. Its revised Royal version did make changes to this, which Atlus confirmed to IGN at the time. However, as Laura Dale detailed for Polygon, the revised scene still involves a lack of consent and remains uncomfortable. Atlus may be learning from past mistakes, but it’s a slow process that leaves the inevitable Persona 6 with a lot to prove.

In purely mechanical terms, P4G still stands as an impressive JRPG. But as an exploration of gender and sexuality, it’s an incredibly disappointing experience that simply doesn’t match the standards of today. And while it can be revered as a relic of the past, its re-release without amendment perpetuates tired stereotypes. We all deserve better.

Be the first to comment