If you’re not familiar with Chinese, have you ever wondered why game localisations tend to have two language options?

There’s Traditional Chinese, which refers to the original Chinese characters that have been in use for centuries in reading and writing, commonly used in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, as well as in many overseas Chinese communities. Then there’s Simplified Chinese, the simplified characters introduced in Mainland China since the CCP came into power in the 1950s, which is the country’s official language.

That’s why localisers usually cater to both Traditional and Simplified Chinese when it comes to translating text. However, when it comes to audio languages, it appears that only Mandarin, China’s official language, is taken into consideration, while neglecting Cantonese, the second most commonly spoken Chinese language. As someone of Cantonese descent, I obviously have a bias here, but it nonetheless had me wondering why this language gets left out in games.

Obviously, there are a few factors to consider. Recording audio isn’t cheap compared to just translating text, and even for big budget games you’re likely to have fewer audio language options compared to text options. So in the event a game does feature Chinese audio, I can see why a publisher might weigh up budgets and consider who’s the more important market to prioritise: China with a population of more than 1 billion, or Hong Kong with just around 7 million?

However, Cantonese resides further than the former British colony. The number of Cantonese speakers is actually around 80 million worldwide, including people from China’s Southeastern province of Guangdong where it originated (both the province and its capital are known in English as Canton), while generations of Chinese immigrants (mine included) in the UK, Western Europe, North America, and Australia came predominantly from Cantonese-speaking regions like Hong Kong, Macau, as well as Guangdong. Many Chinese concepts or phrases that Westerners know, such as dim sum or the happy new year greeting ‘Gung hei fat choi’, are Cantonese in origin. Given that global spread, it actually makes sense to cater to Cantonese speaking audiences as much as Mandarin speaking ones.

Chinese is however a tricky language for others to make sense of, since the written and spoken forms do not neatly correlate. The simplified and traditional characters only refer to the written language, not how it’s spoken. While Chinese text can be read and understood by both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, the characters themselves do not indicate their phonetic variances as the Latin-script alphabet does, which is why it’s easy to conflate the two.

I actually have a strange relationship with the two languages, due to a clerical error that occurred with my dad’s passport, which resulted in the English phonetic translation of our family name being written as Wen, the romanisation of the Mandarin pronunciation, rather than Wan, as it’s pronounced in Cantonese. Adding to this complication, my Chinese family name, 温, is written in Simplified Chinese, and this is oddly what’s commonly accepted in Hong Kong, instead of the traditionally written 溫, with literally one stroke of a difference. (Fun fact: how a Chinese person’s name is romanised will usually indicate if they’re of Cantonese descent, such as with the actor Benedict Wong, whose family name would otherwise be Huang.)

Still, given how Simplified Chinese and Mandarin is virtually synonymous with Mainland China, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to associate Traditional Chinese with Cantonese, or platform holders and publishers should consider differentiating Chinese by region, as is the case with Spanish in Spain and Latin America, and French in France and Canada.

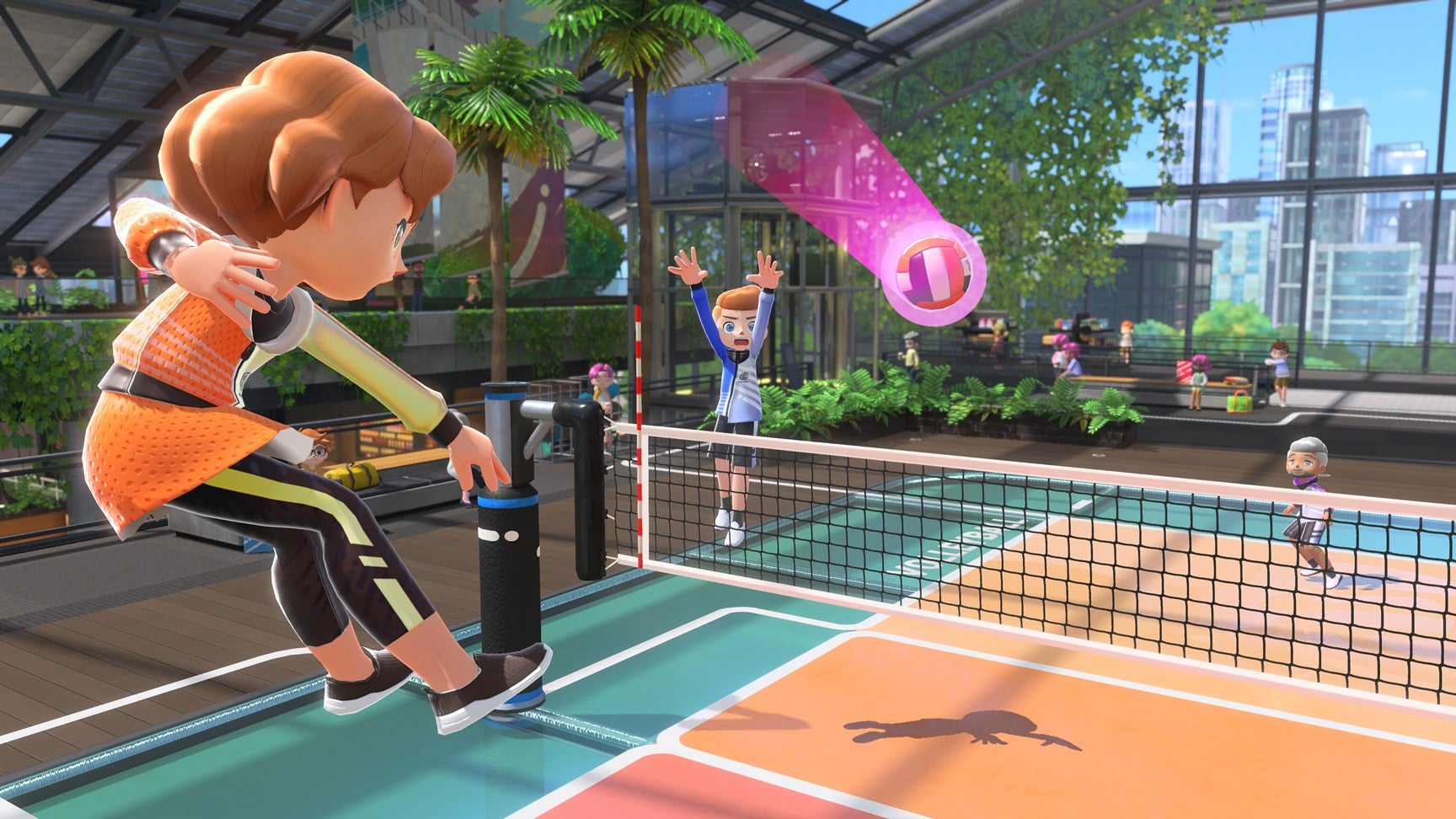

Let’s consider Nintendo Switch, whose audio languages are usually tied to the language set on the console, where it has both Traditional and Simplified Chinese as options. This might not be an obvious example given that Nintendo characters rarely talk or only speak gibberish when they do (although Animal Crossing: New Horizon’s Animalese is actually localised). Nonetheless, casual fare like 51 Worldwide Games and Nintendo Switch Sports do contain spoken audio, but whether you pick Simplified or Traditional Chinese, both only have Mandarin audio.

A more egregious example comes from interactive drama As Dusk Falls. Regardless of opinions over its unusual animated graphic-novel aesthetic, one of the benefits meant that lip sync wouldn’t be a concern, making it possible to localise dubs in a greater number of languages. This was part of Interior Night’s goal to make this experience accessible to a far-reaching non-traditional audience, in the same way the studio also released an app so that the game could be played using just a phone. The game features a dozen audio dubs, including Chinese.

Yet despite containing two different Chinese dubs, one for Chinese Simplified and one for Chinese Traditional (not a very helpful reference since, as mentioned, these refer to the written rather than spoken language), it turns out both are actually recorded in Mandarin.

I’m personally not fluent with Mandarin, though I am aware it has many regional variances that differ from the Standard Mandarin that’s based on the Beijing dialect (similarly, the game features two Spanish dubs, with the other in Mexican Spanish). But if you were going to have two Chinese dubs, surely it would have made sense for one to be Cantonese instead? Publisher Microsoft didn’t respond to my query on this localisation decision, but the oversight is ironic given that the company’s own translation app does cater to Cantonese, unlike Google’s.

It’s also a personal disappointment as I hoped this was a game I could have introduced to my mum. While she plays casual games, I’ve never been able to introduce her to narrative-driven games because she doesn’t speak English, and she’s not much of a reader, so subtitles and anything text-heavy’s also out of the question. While I’m not sure she’d necessarily be interested in a US-set crime drama over her Cantonese shows, a Cantonese dub would have made all the difference.

Another instance of Cantonese being sidelined is action game Sifu, which was noted by critics as a loving if exotic touristy depiction of China by white people for white people. Although Sloclap tries to balance this with Chinese voice-acting added post-launch, there is only a Mandarin dub. It’s a choice that sticks out, considering how the game had drawn comparisons with the Hong Kong martial arts films of Jackie Chan. Even the title itself means ‘Master’ pronounced in Cantonese, whereas the Mandarin pronunciation is ‘Shifu’.

Besides publishers favouring Mandarin audio, I wonder if the virtual absence of Cantonese dubbing in games could be down to a lack of demand or infrastructure. This doesn’t seem to ring true as Cantonese dubbing has existed in other forms of entertainment for decades. I still remember the days when, in trying to get me engaged with my native tongue, my mum would bring home VHS cassettes of Cantonese-dubbed anime she borrowed from friends or aunts, which I’d happily watch and not realise until years later were Japanese in origin.

It’s been a nice surprise to learn that one of the popular anime shows I watched when I was younger, Crayon Shin-Chan, does feature a Cantonese dub in the licensed game Shin-Chan: Me and the Professor on Summer Vacation – The Endless Seven-Day Journey, featuring the same local voice actors from the show. There’s a catch to this, as this is only available in the game’s Asian edition (which also features Mandarin and Korean dubs), whereas the Western release only contains the original Japanese audio.

In fact, Cantonese dubbing (or indeed other languages) for animations continues to be popular on streaming services, where I discovered a very good Canto dub for Aggretsuko on Netflix. Disney+ has even more comprehensive language support, with usually more than a dozen dubs for its shows, including Cantonese. It’s been great watching Pixar’s Turning Red in Cantonese, while my sister has normalised having her kids watch their favourite shows dubbed to help them retain their cultural language, and ensure they’re able to communicate with their grandparents.

If only the same level of consideration went into dubbing video games, which so far seems to have only been demonstrated by Croteam, developer of philosophical sci-fi puzzle game The Talos Principle. As far as I’m aware, this is the only game from a Western company to include a full Cantonese dub. According to a statement from audio director Damjan Mravunac, the decision had actually been very straightforward: “I didn’t have much experience regarding which languages are popular, so I decided to do them all, audio dubbing included. I learned that there are over 200 dialects of Chinese, but Cantonese and Mandarin cater to most of the population in China, so it made sense to do them both, especially since there was not much audio content in TTP1, so it wasn’t that complicated.”

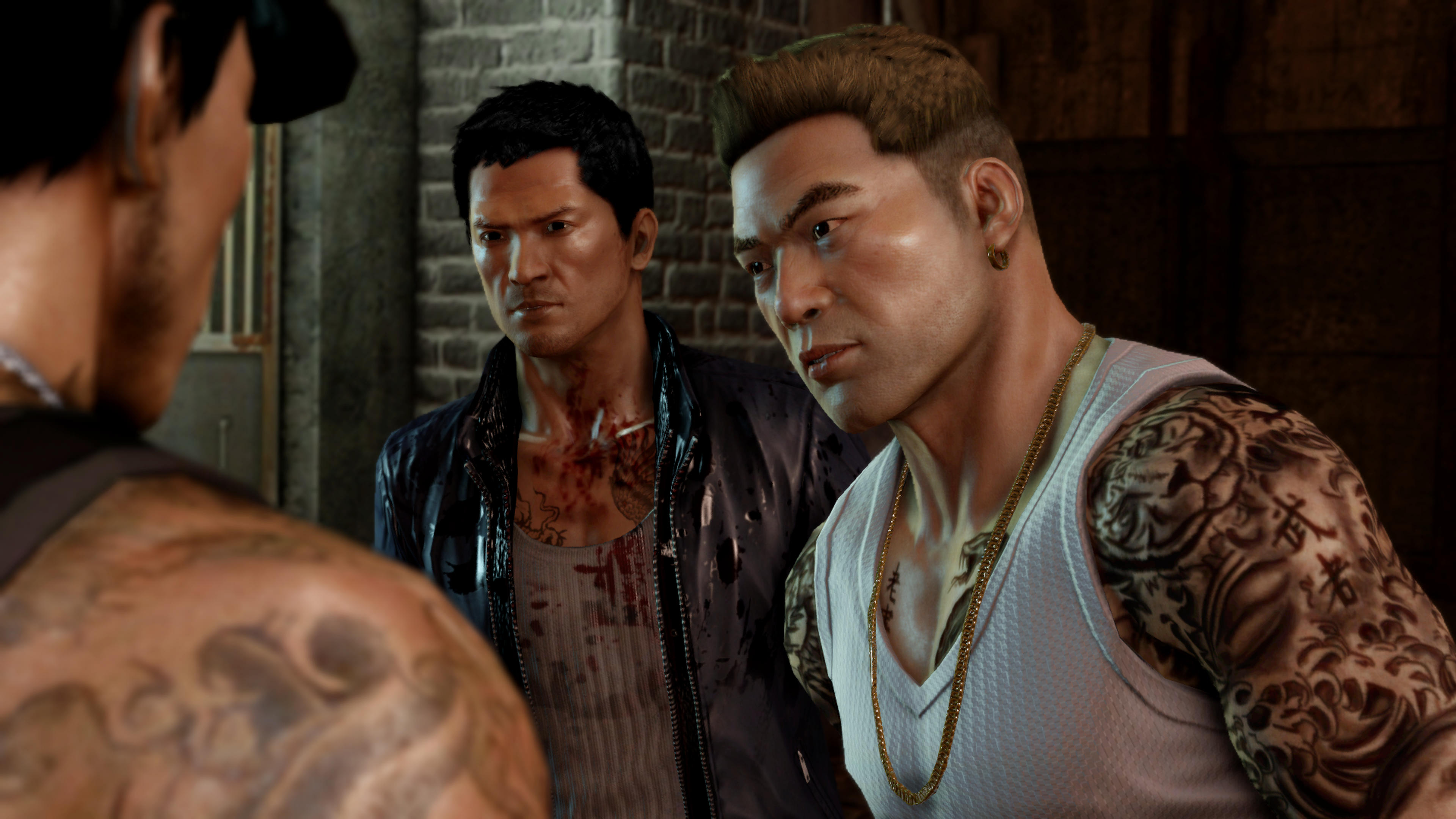

Of course, if we’re going to mention games with Cantonese voices, you can’t ignore Sleeping Dogs, an open world game set in Hong Kong, which arguably features the most Cantonese voice acting in any game to date. It’s certainly shown a lot of progress since the Hong Kong-set action game Stranglehold, which was voiced entirely in English. (What’s stranger is that it was reportedly Hong Kong filmmaker John Woo’s company Tiger Hill Entertainment who decided against any Cantonese VO, despite it being the native tongue of its star Chow Yun-fat while the game is meant to be a direct sequel to Woo’s Hong Kong action cult classic Hard Boiled.)

There’s a caveat to Sleeping Dogs’ Cantonese audio. This is ultimately a game made by a Western developer for a Western audience, so its story is scripted in English with just a smattering of Cantonese (mostly profanity). I imagine part of this is also because, despite having a predominantly Asian voice cast, some of these actors, including Will Yun Lee, Kelly Hu, and Lucy Liu, don’t speak Cantonese. Instead, the majority of the Cantonese comes from the NPCs who populate the city or the radio airwaves. While these are authentic, they’re also reduced to exotic flavourings since none of these are subtitled.

It’s strange for me to write about this given that my Cantonese is actually terrible, which I attribute to being born and raised in the UK, which comes with the cross-cultural baggage of trying to fit in and resenting your own heritage. But while I lack the vocabulary to converse in important subjects like politics, it’s also impossible not to consider the politics of Cantonese being eroded by Mandarin, whether in Hong Kong’s education system, or Nintendo’s decision in 2016 to unify the names of more than 100 Pokémon but according to the Mandarin pronunciations, which disgruntled fans in Hong Kong called the erasure of “the collective memory of a generation.”

I suppose that’s the point of this then, even as I struggle to articulate it in the language myself. Perhaps it’s a last-ditch attempt to preserve and remember this part of my culture before it’s forgotten.

Be the first to comment