A long time ago I was a writer for a games magazine called Edge. I left because I wanted to make games but I kept writing, for myself and for talks that I still irregularly deliver at events. This is one of those, a short (true) story that I never quite figured out a purpose for and I’m pleased it’s finally found a home. If you want an audio version there is one on my never-updated website.

Talking of audio: I co-host a radio show, One Life Left, where we’ve been reading out Eurogamer’s news stories and rating games 7/10 for 16 years — it’s the longest running radio show about games in the world. And I sing pop songs about videogames with you at Maraoke, a karaoke night about games. More info on that here.

Last week I played the Steam version of Dwarf Fortress. It’s everything it needs to be. Tarn is a good man. If you haven’t already bought it you’ll find no better way to spend £30 on games in 2023. 7/10.

INT #1: The Queen

I glance at the clock. It is a little after midnight.

The Queen, not the Queen but another Queen, my Queen, sits on the edge of a cedar chair by the dressing table in her bedchamber, waiting for the knock on the door. When will it happen? Tonight or tomorrow morning, perhaps the day after that, but she knows it will come. And when it does she will rise to open the door and the man on the other side will hang back in the shadows, fearful, shaken. As he steps into the flickering light he will bow his head as normal; usually out of respect, right now because he cannot look her in the eye. She will bite her lip and she will want to say I know, I already know, but that is not how this story goes and besides before she can… “Ma’am,” he will say. “I’m sorry to disturb you, ma’am, but… The King… He’s…”

In that trailing sentence her world will collapse. Her scream will bounce from the stone walls of the fortress, a raw, primal choke that is both guttural and piercing, unforgettable, infinite. All air and life drained from within her, her stomach will buckle and she will fold inwardly to the floor like an unhung tapestry. Somewhere, a button has been pressed that turns light into dark: all their dreams, the plans they made and the stories they have written dissolve to fiction, and the future falls away, dragging the past in its slipstream; it is not just that there is nothing, but as if there has never been anything. There is just here, just this. Just darkness, loneliness, forever.

That’s the future. For now she sits and she waits for the knock. It will come.

All I can do is watch.

Dwarf Fortress is a treacherous game, a videogame like no other. An independent project developed by Tarn Adams, a lone coder who considers the game his life’s work, it simulates the world for a group of Dwarves whose aim is to build a permanent settlement in a high-fantasy wilderness. It is a mixture of Sim City, Dungeon Keeper, Nethack, Microsoft Excel, unfathomable magic and excruciating mental pain.

Dwarf Fortress is also a lonely game. Not just because the Dwarves begin isolated in the middle of nowhere – as with Minecraft, they must immediately carve a temporary first home in the environment before that same environment kills them – but because it leaves the player utterly isolated too: isolated by design, isolated by the interface, isolated by the aesthetic.

Isolated by design: You do not have direct control over the Dwarves. You can issue commands, order them to a certain task or location, and, in theory at least, these commands will be obeyed according to a hierarchical tree of jobs and priorities. In truth this system is at best obstructive, at worst impenetrable, and you are at the mercy of your Dwarves’ desires. Dwarves can be pretty whimsical. As much of your time is spent issuing commands as is finding out why, say, your undertaker is getting drunk and fishing rather than burying the corpse rotting away in his dormitory (he is probably depressed) (It’s almost always depression).

Isolated by interface: The manner in which you direct the dwarves is arcane. Arcane is an overused word in videogame criticism, commonly invoked to describe mysterious inventory implementation or developers choosing the wrong F-key for quicksave.

“It is so… Arcane!” a journalist might wail at an unfortunately placed jump button.

What they mean is “this behaviour is slightly different from the norm” and these cowardly motherfuckers have no place playing Dwarf Fortress, whose interface is the correct definition of arcane: it requires secret knowledge to be understood. That knowledge is impossible to find out by trial and error, the usual way we learn in games, and must be decoded from wikis and readmes and community-created tutorials. You fight the interface at every turn: control flits between keyboard and mouse apparently at random and the purpose of each key changes from screen to screen. To play Dwarf Fortress – and by play I mean execute even one command successfully, to consider an action and have it play out on screen – is an achievement that makes people who know about Dwarf Fortress gasp in awe.

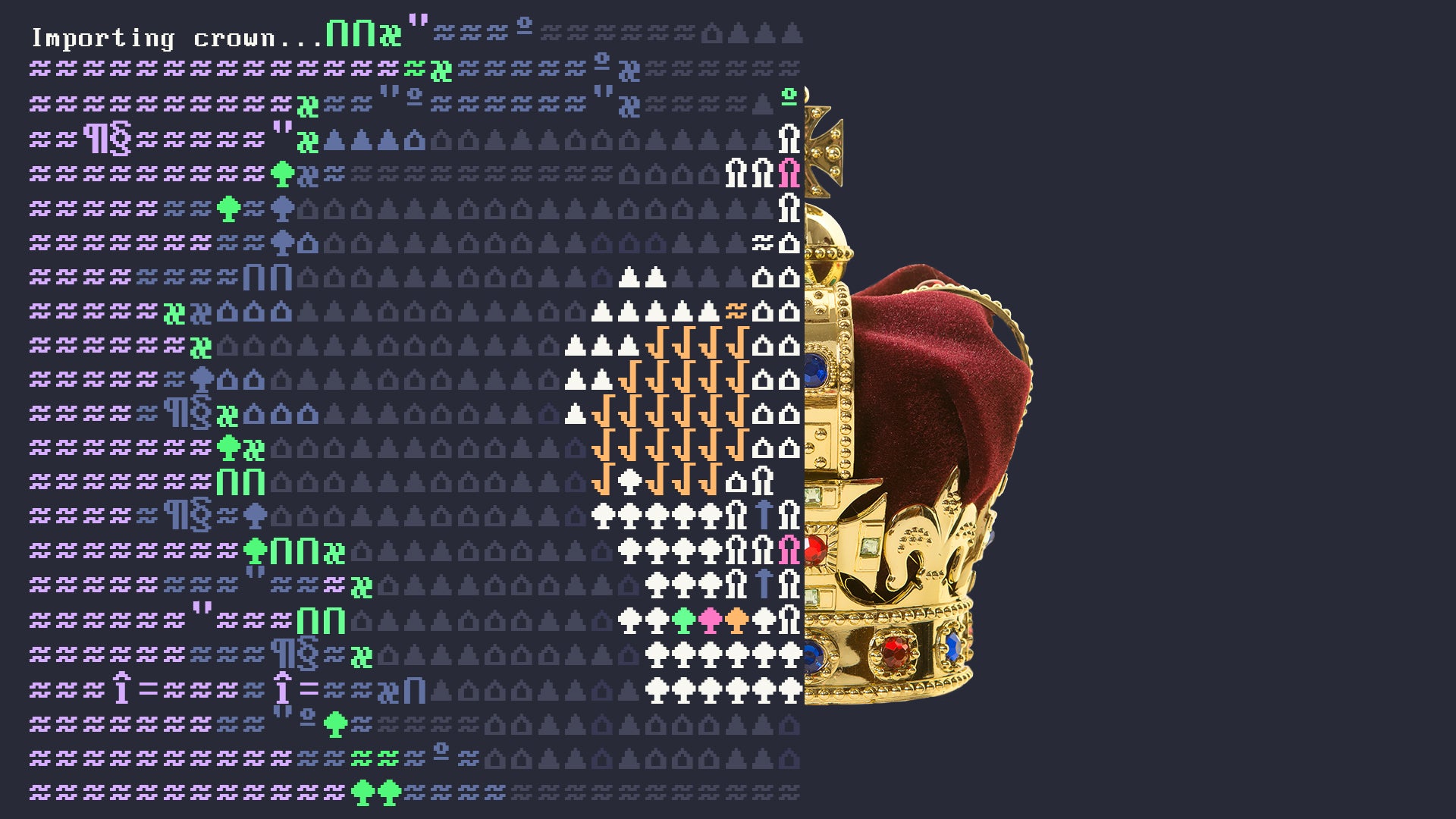

And finally, crucially, isolated by the aesthetic. Everything in Dwarf Fortress is shown through an ASCII cipher, the letters and numbers you might find in a word processor arrayed on a regular grid. There are no graphics at all which means manually translating each on-screen symbol, block by block, into something you can understand. A smiley face is a Dwarf. A blue tilde sign is a section of a river. A green apostrophe is a patch of grass until it is stained with blood, and then it becomes a red apostrophe, stays red until the rain washes the blood away.

Each of those three points means Dwarf Fortress is all but inaccessible to the vast majority of people. Even those of us who have played, beaten and built videogames our whole lives need to work ludicrously hard to arrive at a point where we can say we have experienced the game. It took me eight weeks of studying, before I could say I could “play” Dwarf Fortress, and “play” did not mean “survive”: it meant being able to load the game, issue rudimentary commands to my Dwarves and, soon, to read their grim deaths, visualise their cold corpses burrowed into muddy holes in the ground.

But the way the game isolates the player and forces them to learn a new language is also its biggest triumph. You begin as an observer, your experience shrouded in fog, but when that fog finally lifts you find the world is entirely yours. When I see those symbols on the screen I do not read them as symbols any more than you hear these words as loose collections of letters. They are the grass, the blood, the rain: my dwarf, my Queen.

She bites her lip, she wants to say I know, I know…

There are no missions in Dwarf Fortress, just stories you write yourself, tales that cascade from the cracks in the unique systems you create. It is your job to keep your dwarves alive for as long as possible, spin the plates before they fall. Your fortress becomes larger and larger and eventually the friction between the tiny components in your intricate design throws up sparks, literal and metaphorical, and things soon burn out of control.

To fan the flames – the game’s official motto is “losing is fun” – Dwarf Fortress throws problems at you as you progress: goblin invasions, food shortages, harsh weather, dragons. When your fortress reaches a certain size it attracts the attention of Dwarven Royalty who move in and issue production laws. A small part of the screen shows a constantly scrolling text box, describing the things going on around you. It serves as the game’s inner monologue and informs you of important events – births, deaths, marriages and so on – and when the royalty arrive it keeps you informed of their demands: the Queen insists you cease production of glass immediately, the King decrees you must produce cutlery carved from tiger bone. These demands, constantly changing, will stretch your resources to the limit. But you will obey because that is the game. It is part of your story.

I loved and hated my King and Queen, just as the game intended, right up until the day the goblins came and everything changed. By chance the invasion caught the King drunk and fishing just outside the castle walls. As soon as he saw them he knew, he knew; he rose to his feet and an arrow struck him in the chest. Two stumbling steps towards the drawbridge and the goblins were upon him, swarming, slashing, turning the land from green to red. Just moments later the guards stormed from the gates and slaughtered the goblins, too late, and then within the hour the knock on the door came, the Queen sank to the floor and her scream echoed and…

Something happened. I don’t know if this was by accident or design– Dwarf Fortress is full of hundreds of bugs which means that sometimes it’s difficult to tell glitches from features and there lies some of the game’s humanity – but no sooner had the old King been buried then at the edge of the map another King and Queen appeared. Noting that my thriving fortress had lost its ruler, the game had gifted me a new monarch.

At first I was delighted. I built a new royal bedroom, decorated it with the plushest furnishings and soon my new rulers made themselves at home. They, too, began issuing manufacturing orders, as Dwarven royalty is code-born to do – coexisting (but never communicating) with the Old Queen, my Queen, a near-silent shadow. I watched her ghost around the fortress – drifting through the fields, picking flowers and heading to her husband’s grave. She sat alone in the dining hall for hours and hours and she, too, would make demands – make weapons from Goblin bone, lots of them, all of them. The trouble with vengeance is that it always comes too late.

She was a living scar and every time I saw her my conscience twitched: could I have saved him? Could things have been different? It troubled me but the real problem was more practical: my fortress was built to survive the production demands of two royals, not three. Our food reserves were eaten away, our army was stretched to breaking point; camp-wide disease and depression crept in, nestled next to the overworked Dwarven proletariat as they slept. Tempers flared, sparks started to fly and I could see my story coming to a close. But I’d worked so hard for this, late into the night, and to think it was all going to collapse because of one stray arrow, one sad Queen, and there was nothing I could do… Except…

You can’t remove citizens from Dwarf Fortress. There’s no, simple, clinical delete unit button, no way to vanish the ones into zeros. You cannot tell your Dwarves to kill themselves.

But you can kill them. Not directly, not easily, but there are ways. Arcane ways.

So it was I resolved to build a drowning chamber.

I designed a room. A small, simple room, three tiles by three, close to my cemetery . Outside the room, there would be three buttons: The first button locked the door, sealing the victim inside. The second button filled the room with water, tight to the ceiling. The third button opened a grate at the bottom to drain my makeshift cistern. That would allow me to remove the body. Her body.

The drowning room could not be constructed overnight. It would take some months in my stretched fortress, over half a year of game time in fact, time that weighs heavily upon the curator of a murder. I did my best to avoid her gaze but now my Queen was everywhere, drifting aimlessly, always reminding me. Sometimes she’d wander past the construction site. “What’s that…” she’d murmur, half-heartedly, but she knew, she knew, just like she knew the knock was coming she knew…

It was three months into construction that I realised this wasn’t how the story could end. I couldn’t bundle my Queen into a room, drown her, have the rest of her people move on with their lives as if this was somehow normal. Even though she’d submit willingly, even though she saw no future and craved nothing more than death, this wasn’t right.

So I wrote a new ending. I retrieved some obsidian, one of the rarest types of stone in the game and almost invaluable in my current location. I’d been saving it to craft into something special and this was that thing. I ordered my finest artisan to sculpt a statue of the old king and stood the statue in the centre of the drowning chamber. I moved the second switch, the button that would fill the room with water, inside the room. I placed the switch on the statue’s hand.

And here is what was going to happen.

One morning, a bright and sunny morning, my Queen would wake as usual and walk to the cemetery. There she would remove her wedding ring, lay it on her husband’s grave and give the headstone a gentle kiss. And finally free of burden, casting off the weight of that scream, she would walk to the chamber I had built.

Inside the chamber, she would stand in front of the statue of her husband and look him in the eye. She would remember the plans they had made for this place, their home. She would think about her life before that scream and know the past really did exist – that even if the story, their story was over, it had been told and that was enough – and she would smile, she would finally smile. She wouldn’t hear the door lock behind her. She wouldn’t care. She’d close her eyes, she’d embrace the statue, she’d place her hand on his.

And then…

Construction is finished and the morning arrives. It is bright and sunny and my Queen wakes, and it should be clear right now that I am talking myself into doing this, still, but I am almost at peace with my decision and the Fortress is in trouble so something must be done. The statue is hauled into place and the Queen heads from the graveyard to the chamber. She walks into the room and I tell another dwarf to lock the door. He runs away immediately afterwards. It is as if he knows.

And there, looking down on a 3×3 text grid that represents love, death, the beginning and the end, I wait for the Queen, my Queen to push the button.

She doesn’t push the button. She’s thinking. She’s still thinking. Why is she still thinking?

Suddenly I see it: there are two people in the room. She’s not alone.

STOP. STOP. Something’s gone wrong. My eyes tick instinctively to the status messages as I try to work out what’s going on. And this is what I read:

“The Queen has given birth to a Baby Girl.”

Impossible, I think. That’s impossible. She’s been alone since the King died. And he died nine months ago…

Holy shit.

She can’t do it. I can’t do it.

I open the door.

Three months of game time later the sparks, metaphorical and all too literal, rage out of control and the fortress burns to the ground. Everyone inside dies: The New Queen, the Old Queen, her three-month old daughter. Everyone. There’s nothing I could have done, I tell myself, as I glance at the time – 3AM – and then down to my computer’s off switch. I stand up, I push the button and all the plans I have made, the stories I have written dissolve once more to nothing.

Be the first to comment